Introduction

In the realm of sports and physical activity, anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury has emerged as a prevalent concern, particularly among female athletes. As a physiotherapist and clinic deeply invested in the well-being and performance of athletes of all levels and commitment, it is crucial to shed light on the unique challenges that women face when it comes to ACL injuries. While both men and women are susceptible to ACL tears, research suggests that females experience a higher incidence rate and often encounter distinct risk factors. We aim to enhance understanding and promote effective prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation strategies by delving into the intricacies of ACL injuries specific to women. This article seeks to empower athletes, coaches, and healthcare professionals with the knowledge necessary to safeguard women against ACL injuries, enabling them to thrive in their athletic pursuits however serious or casual.

Anatomical, Physiological, and Biomechanical Differences

Male and female athletes have anatomical and physiological differences that can significantly impact their sports performance. These differences include variations from the micro-view of our physiology to the macro-view of our anatomy such as our bones, ligaments, tendons, and muscles.

Physiologically, it has been found that tendons’ stiffness, failure load, collagen content, and fibroblast proliferation may be influenced by estrogen levels, a hormone found in both sexes but fundamentally more in women (especially those of reproductive age). Pregnancy, hormone substitution, oral contraception, estrous cycle, and menopause are some common causes of estrogen level changes during the life of a woman. (LeBlanc et al., 2017)

In terms of physical differences between men and women, there are some notable variations. Generally, men tend to have more muscle mass and lean body tissue, while women tend to have a higher proportion of body fat. The way fat is distributed in the body also differs between the sexes, with men typically storing it in the trunk and abdomen, while women tend to store it in the hips and thighs.

One of the most noticeable skeletal differences is found in the pelvis. Females have a wider, oval-shaped pelvis, which is adapted for childbirth, while males have a narrower pelvis. This impacts the width of the pelvic inlet and the movement of the coccyx, commonly known as the tailbone.

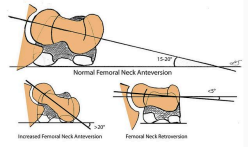

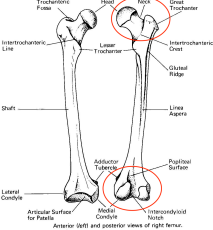

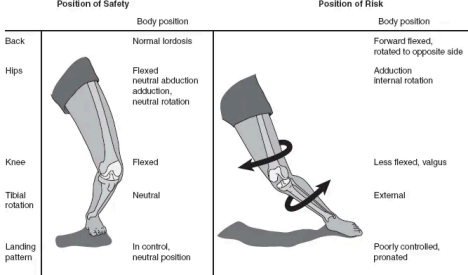

Moreover, there are anatomical variations between men and women that can increase the risk of ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) injuries. Two specific factors come into play: femoral anteversion and the Q angle. Femoral anteversion (Fig. 1 & 2) refers to the orientation of the thigh bone’s neck in relation to the bony landmarks at the bottom of the thigh bone, near the knee. The Q angle (Fig. 3 & 4) is formed by connecting two lines from specific anatomical points. These factors can potentially affect the forces on the shin bone and cause excessive torsion, leading to pronation in the subtalar joint, one of the major joints in the upper ankle (Fig. 5).

These biomechanical deficiencies in an individual’s anatomy may predispose them to a higher risk of ACL injuries.

|

| Fig. 1: A visualization of femoral neck

Fig. 2: Reference points for the anteversion variations. understanding of the location of the femoral neck and femoral condyles |

|

| Fig. 3: A visualization of a Q-angle. Fig. 4: A general trend of Q angle difference between females and males –

Females tend to have a larger Q Angle, which is believed to affect one’s biomechanics. |

Fig. 5: A visualization of the biomechanical deficiencies that predisposes one to a higher risk of ACL injury.

Statistics on Injuries of Female Athletes

In women, the total number of days missed due to absence was 21% higher. This was mainly because they experienced severe knee and ankle ligament injuries 5.36 times more often. Men, on the other hand, had more cases of hamstring strains and pubalgia (pain around the pubic region), occurring 1.93 and 11.10 times more frequently, respectively. Women had higher rates of quadriceps strains, anterior cruciate ligament ruptures, and ankle syndesmosis, also known as high ankle, injuries, which were 2.25, 4.59, and 5.36 times more common, respectively.

The Verdict

At HKSC+, our physiotherapists will play a crucial role in your journey to preventing ACL injuries through the implementation of a comprehensive rehabilitation protocol. By assessing an individual’s specific needs, and strength and biomechanical deficiencies, a physiotherapist can design a tailored program to address muscle imbalances, improve strength and stability, and enhance balance and proprioception. This protocol may include exercises to strengthen the muscles around the joints of the lower limb such as the ankle, knee, and hip, balance training, agility drills, and (neuromuscular retraining techniques. Additionally, we will educate you on proper body mechanics, injury prevention strategies, and sport-specific techniques. We also aim to empower you to regain optimal function, reduce the risk of ACL injury, and return to your physical activities with confidence and resilience.

If you are a female athlete and would like to work with us, don’t hesitate to reach out via E-mail: appointments@hongkongsportsclinic.com

E-mail: appointments@hongkongsportsclinic.com

Phone: +(852) 3709 2846

Instagram: @hongkongsportsclinic

(https://www.instagram.com/hongkongsportsclinic?igsh=bzh5bHlzZzJobW9q&utm_sour ce=qr)

In conclusion, prevention strategies should be tailored to the needs of male and female football players, with men more predisposed to hamstring strains and hip/groin injuries, and women to quadriceps strains and severe knee and ankle ligament injuries.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/sms.12860?platform=hootsuite

Understanding these physiological differences between males and females is essential for tailoring training programs, injury prevention strategies, and optimizing performance for athletes of both genders.

Females are more prone to certain anatomical variations, such as increased Q-angle, tibial torsion, and femoral anteversion. They also tend to have greater general joint laxity compared to males, and estrogen levels can affect ligament stiffness.

Bone health is another area of difference. Approximately 50% of females will experience an osteoporotic fracture in their lifetime. Bone density measurements, such as DEXA scans, are used to assess bone health. Exercise, however, is a preventative method for this and plays a crucial role in optimizing bone health, as bones undergo gradual adaptation to habitual loading it is engaged in. Implementing a progressive dynamic loading with moderate to high strain magnitudes and rates could potentially be beneficial.

Tendons, which transmit mechanical force from muscle contraction to bone, also have gender-specific characteristics. Females have a lower rate of new connective tissue formation, less response to mechanical load, and lower mechanical strength than males.

When considering female athletes’ performance, factors such as muscle mass, strength, anaerobic power and capacity, and muscle cross-sectional area should be considered.

Size of intercondylar notch in the femur and diameter of ACL is smaller in females than in males. (however there hasnt been any research on the correlation between size of ACL and injury risk so far.)

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960076017301590